4 Reasons AI Won't Take Developer Jobs

As I write this, there is hand-wringing all over the Internet due to the advent of code-writing AI tools like Github Copilot and ChatGPT. Developers everywhere are, understandably, somewhat concerned.

These tools can take requests (“prompts”) in plain English and produce shockingly accurate computer code, in almost any language you’d like, that fulfills the request. If you squint a little, this is uncomfortably close to the daily work of the software engineer; many developers spend a good portion of their days having a task described to them in plain English, then writing code to tell the computer how to perform the task.

If computers can do that themselves, what happens to the demand for developers?

Here are 4 reasons that, in my view, developers can breathe easy for now.

Developers as Specificity Engineers

By the time a developer has attained a senior rank, they usually realize that part of the job – in many cases, most of the job – is not actually programming. These two things become more and more true the further you go in your career:

- Your clients – whether customers or your own boss – don’t actually know what they want.

- Knowing what to build is more important than knowing how to build it.

A good part of your job is working with your client to figure out what they actually need, which is often very different from what they think they need. Clients often don’t even have the right words to use to describe what they need. They have problems, not solutions.

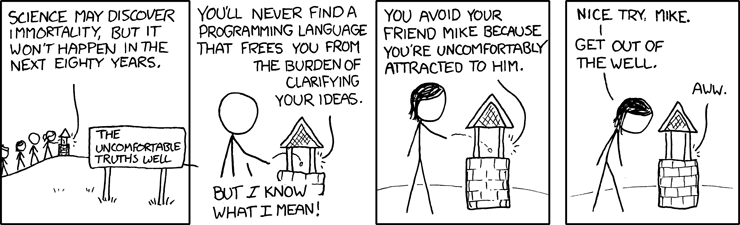

Put another way, the art of software engineering is, in many ways, an art of specification. By this I don’t mean writing specifications, but rather making things more specific.

A software engineer looks at tasks that are vague or ill-defined, and begins to make them more concrete and specific by applying designs and clarifications to them. Eventually, through intellectual effort, the design becomes so unambiguously specific that it can be expressed in code and executed by a computer.

AI isn’t a good tool for making things specific, because the technology is fundamentally a guessing engine. If you give it a task and ask it to write code to address the task, it won’t ever ask you to clarify your intent. Instead, it just generates a plausible interpretation. It is effectively selecting, more or less at random, from a large universe of possible interpretations of the input. That’s helpful, sometimes, but it isn’t what an engineer does.

AI-Augmented Developers

If you are adept at using AI, you can become a lot more productive. Developer productivity is notoriously difficult to measure in any meaningful way, but anecdotally, many engineers are finding that Copilot (and friends) can make them 10-40% faster at writing code, and ChatGPT (and friends) can save hours of searching the internet every week.

My own experience bears this out. ChatGPT, Copilot, and Claude help me write boilerplate code, find documentation and examples, and create tests. They are also excellent rubber ducks when I’m debugging difficult problems.

AI isn’t going to take your job; it’s going to do the reverse: make you more valuable by making you better at the job you have.

This Has Happened Before, Several Times

If you’re a young software engineer, this may be the first time in your career that you have been told a technology will replace you. It’s scary. But it’s not new. The software industry invents a new technology every 5-10 years that is supposed to replace software engineers. It never does.

- In the 1980s, fourth-generation programming languages were supposed to replace software engineers. They didn’t.

- In the 1990s, CASE tools were supposed to replace software engineers. They didn’t.

- In the 2000s, model-driven development was supposed to replace software engineers. It didn’t. Neither did visual programming.

- In the 2010s, low-code platforms were supposed to replace software engineers. They didn’t.

Every time a new technology appears that is supposed to replace software engineers, it makes them more productive and valuable instead. History suggests that this latest round of AI tools will do the same.

Demand for Code and Jevon’s Paradox

In the 1800s, the Watt steam engine was introduced. It was dramatically more efficient than previous steam engines, consuming far less coal for the same unit of work. Experts predicted that this would lead to falling demand for coal, because now you needed less of it to do the same task. Makes sense, right?

However, Watt’s engine actually caused exactly the opposite effect – coal consumption rose instead of falling. This is Jevon’s Paradox, an economic principle that states that as technology progresses, the efficiency of resource use increases, but the rate of consumption of that resource also increases.

There is an almost inexhaustible demand for software (it is, after all, “Eating the World”), and the result of making software development more efficient is not less demand for software engineers, but more.